Follow the money

How much does our food system cost? Who wins, who pays?

The UK’s food sector is:

the ‘beating heart of our economy’, generating £153 billion of economic activity and employing more than 4.2 million people.

and/or…

a chronic disease generator that costs £268bn each year via lost lives, lost health, lost productivity.

A fascinating new report ‘Net Gain or Net Drain?’ was released by the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission (FFCC) last week. Written by Dolly van Tulleken and Hannah Haggie, it sets out the results of a scoping project to identify an approach to assess the full performance of the UK agri-food system.

The foreword by Tim Jackson (who wrote the report that led to the headline above, a year ago) dives straight in:

‘What does it tell us when a Labour MP hosts a 60th birthday party for KFC in Parliament and a Conservative MP declares that she had a “cluckin’ good time” there?’

Does Big Food generate a net benefit to UK citizens – or does it represent a ‘massive false economy?’

What’s clear is value cannot be captured by economic metrics alone. Any measure needs to incorporate fairness, healthiness and sustainability – effects on people and planet – that go well beyond short-term corporate profit.

But who gets to determine the values and metrics we use?

The authors’ response is simple – we do!

Citizens decide. The ground work is already there in the form of the Food Conversation – FFCC’s comprehensive programme of deliberative conversations with UK citizens. Many of whom expressed profound frustration with how the current food system works in practice. They want change.

Results from the Food Conversation were used to develop a framework based on a set of 15 value components, or themes, within four categories:

Future work aims to:

shed light on whether Big Food is generating net-positive value to the public, or whether it represents a net drain?

identify policies, regulations and market structures to ensure the food industry contributes to improving the lives of citizens

Results are intended to help assess progress towards the UK government’s food strategy goals. Next steps include refining the framework and calibrating the targets, developing a set of metrics to undertake a value analysis on a sample of companies, evaluating market power dynamics and finally, to develop a values dashboard to monitor and communicate the performance of the food system over time.

Cost-of-profit crisis

The UK Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, announced in last month’s budget that supermarket giants will face a new ‘surtax’ – a higher rate of property tax, the proceeds from which will help support independent grocery stores who are struggling to survive.

Despite this being just a quarter of what was originally proposed (following industry pressure), it was still preceded by a threat from the British Retail Consortium that such a tax would lead to closure of 400 big stores, a loss of 100,000 jobs and food price hikes.

Apparently this was said with a straight face – at a time when profits raked in by the big supermarkets were soaring! The largest, Tesco, just smashed its record profit of over £3 billion.

‘This is greedflation at its worst – weaponising inflation in the name of fatter profits. The supermarkets are making staggering amounts of money while record numbers of British farmers are going out of business.’ [Guy Singh-Watson, Riverford founder]

95% of food consumed in the UK comes from just ten supermarkets which means we’re hostages in this drama. High-street power means supermarket giants will continue to make mega-profits – as the pain of any financial hit is offloaded to low-income households struggling to afford a healthy diet.

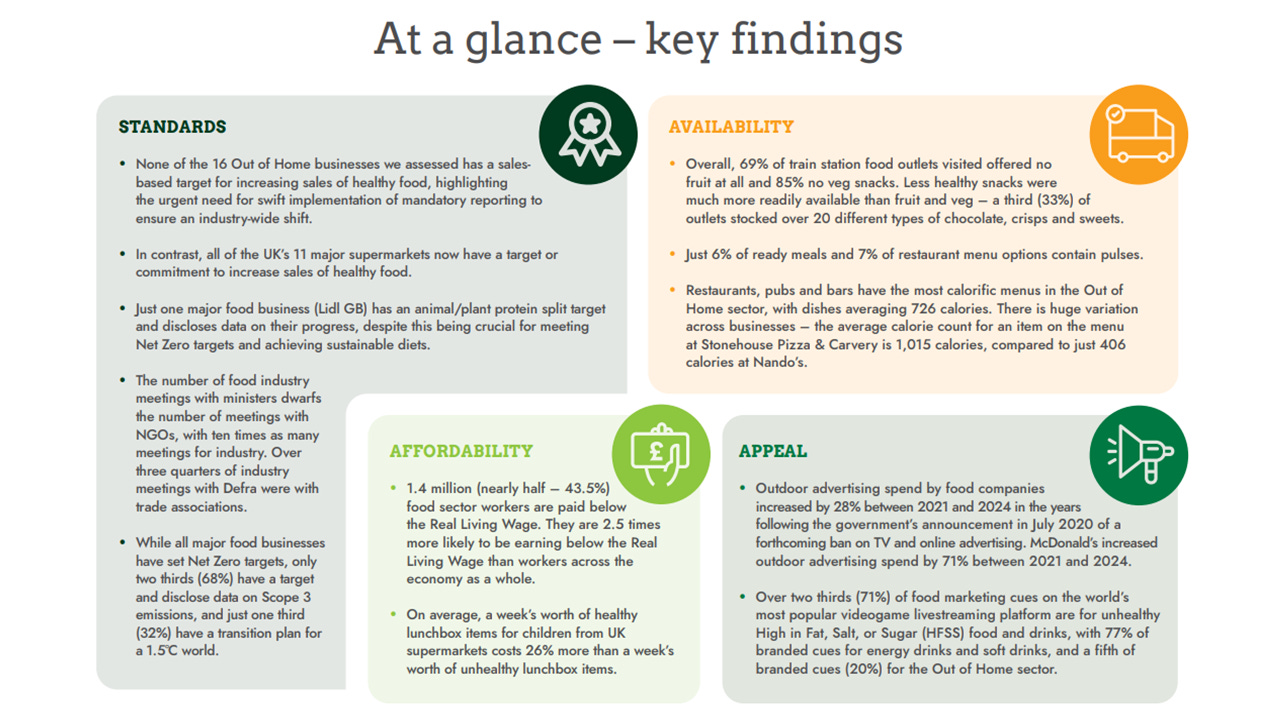

State of industry

The second pivotal report released last week was the Food Foundation’s annual flagship State of the Nation’s Food Industry report. This explored the progress of 37 of the UK’s major food businesses in meeting their climate and health targets, finding progress to be patchy and uneven.

Regulation is urgently needed. The report calls for government-mandated public reporting by companies of a core set of healthy and sustainable diet metrics – to level the playing field and ensure that all businesses are moving in the right direction.

The SOFI also updates the picture on corporate lobbying. Following earlier work by the Food Foundation, in which I was involved, we can see two interesting trends since the new Labour government came in July 2024.

First, industry is meeting more with the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) than with the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) – presumably making the case for industry as a ‘net gain’ generator of economic growth.

Second, there’s been a steady rise in the number of food industry meetings over time – from 37 in third quarter 2024 to 125 in second quarter 2025 – presumably pre-empting future regulation being considered in the national food strategy.

I use the word ‘presumably’ here because we don’t actually know.

Lobby disclosure remains opaque and inconsistent. We don’t know about meetings with senior civil servants and influential spads (special advisors) and we don’t know about emails, phone calls, cocktail party conversations, meetings on the golf course.

Carpe diem

The SOFI report highlights a big challenge which is how to insulate any progress against the whims of politicians in their fleeting time in power?

Government must seize the opportunity to ensure the UK food system serves people and planet and that this new purpose is bullet-proofed across five-year electoral cycles.

‘A Food Bill – focused on ensuring that affordable, nutritious food is a mainstay of living in Britain now and in the future, and locking in improved national food security – would provide a mechanism for ensuring the transition towards a Good Food Cycle that is so urgently needed.’

The unfathomable cost of M&Ms

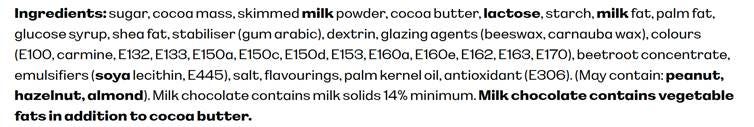

Getting a handle on the environmental cost of food is not easy, but it’s nigh on impossible with many UPF products with multiple ingredients.

M&Ms have 34…

…from 30 countries – each with its own supply chain that transforms the raw materials into ingredients – cocoa into cocoa liquor, cane into sugar, petroleum into blue food dye.

As an aside, there’s an interesting historical parallel here. Here’s an excerpt from the chapter on the colonial food regime in my book:

‘Sugar continued to drive the imperial project. Our craving for sweetness is a product of empire that is still embedded within the annual ritual for Christmas pudding, in which numerous ingredients came together from different colonised countries. Sultanas from South Africa, raisins from Australia, Canadian apples, eggs from Ireland, cloves from Zanzibar, demerara sugar from the West Indies, cinnamon from India and brandy from Palestine. Only the breadcrumbs were home-grown.’

More than a century later, M&M ingredients travel across the world to a central processing facility where they are combined and transformed into multi-coloured buttons.

We know more about food system’s effect on climate change, the effects of deforestation for agriculture, or methane emissions from livestock. But it’s so much harder to get a handle on the environmental impact of UPFs. Multi-ingredient industrial formulations have gone through so many complex processes, it’s almost impossible to track.

CarbonCloud in Sweden have tried though. They estimate that M&Ms emit at the very least 3.8m tons of carbon dioxide per year, probably a lot more.

Even if they could measure it, companies have little incentive to disclose their environmental footprint. As David Bryngelsson, CarbonCloud co-founder says:

‘Most of the people in the [food industry’s] value chain don’t care about climate change from an ideological point of view, but they do care about money’.

Again, to shift those incentives, the true measured value of products needs to incorporate impacts on climate. That in turn will require government regulation and financial penalties based on the true environmental cost of UPFs.

What next?

Doritos apparently have even more ingredients than M&Ms – 39 in total – corn being just one.

PepsiCo recently announced ‘Simply NKD,’ a new variant chip stripped of artificial dyes and flavors that the company views as innovation ( ‘If we can reinvent Doritos and Cheetos, imagine what’s next.’)

Which brings us to this pithy post by the excellent Mike Lee on the problem with naked Doritos.

‘What’s next is more of the same—slightly reformulated versions of the same ultra-processed products, each one stripped of whichever ingredient happens to be trending on social media that quarter, each one marketed as revolutionary while changing nothing about the fundamental business model that made these products problematic in the first place.’

Reformulation is innovation that keeps business as usual. Generating different variants is one way to keep manufacturing desire – when what’s actually being sold is pretty much the same as before. Which is why there are over a hundred flavours of Pringles.

Where next?

Another way to keep growing, to maximise profit is to expand geographically.

A recent analysis of market data from 54 countries and financial data of fast-food retailers examined trends in sales, market dominance, and financial performance.

As sales stagnate in high-income countries, firms maintain profit margins and high shareholder returns via franchising and private equity ownership. Corporations are expanding further into the global South.

The paper recommends policies to target structural leverage points – for example, democratising corporate governance, reducing the influence of private equity, and re-orienting agri-food subsidies, to drive a more democratic, sustainable and healthier food system.

UPFs and children

Last week, UNICEF released a new state-of-the-art review that builds on the 2025 Lancet Series on ultra-processed foods and human health and UNICEF’s own Feeding Profit report to consolidate evidence on UPFs and their implications for children’s nutrition, health and well-being. Chapters by multiple authors from around the world review the evidence on UPFs, sugar-sweetened beverages and commercially produced foods marketed for infants and young children – concluding with a case study from West Africa. The goal is to inform and impel action to protect children from predatory commercial forces flooding their food environments with UPFs.

On the cusp?

Time for some good news…

My 4 November post concluded thus:

‘Turning points are usually only seen in the rear-view mirror, with the benefit of hindsight. Are we in one now?’

An historic lawsuit filed last week makes me think we may be.

Filed in San Francisco Superior Court on behalf of the State of California and led by the city’s attorney, David Chiu, it seeks unspecified damages for the costs borne by local governments to treat residents whose health has been harmed by ultraprocessed food.

Ten corporations are being sued – Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Kraft Heinz, Post Holdings, Mondelez International, General Mills, Nestlé USA, Kellogg, Mars and ConAgra Brands. All stand accused of ‘unfair and deceptive acts’ in how they market and sell their UPF products, in the full knowledge they make people sick.

‘It makes me sick that generations of kids and parents are being deceived and buying food that’s not food’ Chiu told the New York Times.

Earlier this year, California passed a bipartisan bill that became the first in the US to provide a statutory definition of UPFs, and laid a foundation for banning them from schools.

The San Francisco city attorney’s office has a strong track record – with successful past lawsuits on tobacco, lead paint and opioids.

Here’s a clip of the announcement.

We watch and wait…

Best of 2025

It’s that time of the year.

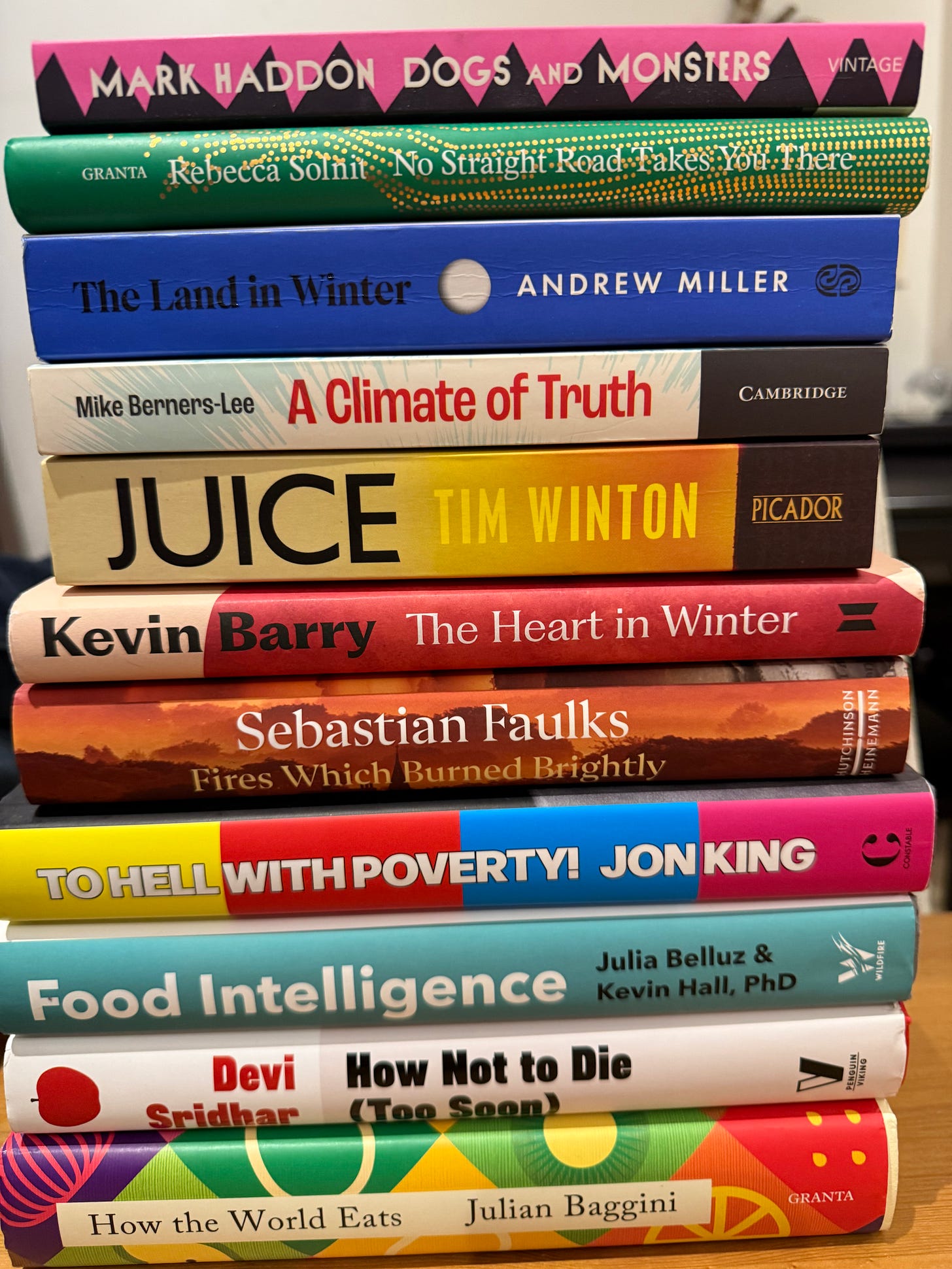

First, here are my best books of the year:

Other mighty reads (not in pic) include Jennifer Clapp’s Titans of Industrial Agriculture, Keetie Roelen’s The Empathy Fix and Austin Frerick’s Barons.

Second, music. Well, it’s been a strange old year really. The only new album I’ve really listened to is Anna von Hausswolff’s brilliant Iconoclasts.

I’ve been leaning in to nostalgia, perhaps a bit too much this year, with these three: Peter Murphy (Silver Shade), Suede (Antidepressants) and The Cure (Mixes from a Lost World).

And, for all the best reasons, revisiting the legendary Gil Scott-Heron.

Here he is performing the magisterial Reagan take-down ‘B-Movie’ in 1982, the year I saw him in London.

It’s winter in America…

That many flavours of Pringles & no longer any dark chocolate Bounty. For me an utter dystopia!