Spring forward

Including cartel capers, escape hatches, fence vs ambulance dilemmas, the passing of bucks and books...and the latest on an ultra-processed food fight.

Nova vs. Novo

First, a quick update.

In my last post, I wrote about the attempt by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and industry-funded scientists to appropriate the NOVA food classification. Before this, there was a widely-circulated open letter and there have been many articles, blogs, social media posts and interviews in the last few weeks. Sunlight has flooded in.

The Financial Times ran with an article highlighting one of the leader’s past consulting work for Ferrero, McDonald’s, McCain Foods and Nestlé. Arne Astrup is head of obesity and nutrition at Novo Nordisk Foundation – it was his original idea to revise NOVA.

A few days later, I was called by a journalist for Dagbladet in Denmark to ask why I had signed the open letter. To me, there are three red flags:

Conflict of interest in the donor, Novo Nordisk Foundation (it’s laughable to argue there is an impenetrable firewall between the company and foundation)

Conflict of interest in key scientists involved, who are currently or have recently taken funding from the UPF industry (such conflicts cannot be managed by disclosure)

Appropriation of the term NOVA by suggesting they were developing the next generation ‘NOVA 2.0’ — made even worse by the fact the NOVA co-founder, Carlos Monteiro, had expressly asked them to desist.

But then, up popped various spokespeople for the ultra-processed food industry to suggest that implying there was any serious conflict of interest in this was — take your pick — ‘unscientific, unprofessional or ideological.’

It’s amazing how often these terms are used to denigrate anyone who dares to raise objections to blatant conflicts of interest.

One of the more vocal, Marcia Terra works for the International Food Information Council (IFIC), an organisation that — surprise, surprise — is funded by pretty much every Big Food company there is. Ms. Terra wrote: “If we truly care about improving nutrition, we need all stakeholders at the table, including industry, academia, and public health experts.”

What’s wrong with this? Well, just who truly cares about improving nutrition? Why would the UPF industry care? Its profits derive from products that generate malnutrition, not improve it. The sentence implies a common goal where none exists. UPF manufacturers care about profit, not improving nutrition – and the pursuit of profit at all costs (ours) is anathema to the pursuit of public health.

Especially irksome in all this is the posturing of many industry-funded researchers as custodians of science and progress while the rest of us are seen as rabid zealots.

The multiple scientific papers that show that conflicts of interest, in the aggregate, generate systematic and significant biases that cannot be managed by disclosure are ignored completely.

Inconvenient science has generated an inconvenient truth — that conflicts of interest like this need to be avoided, they cannot be reconciled.

One of the project leaders, Susanne Bügel has since stated the project will go ahead but without using the name NOVA 2.0.

Food system as escape hatch

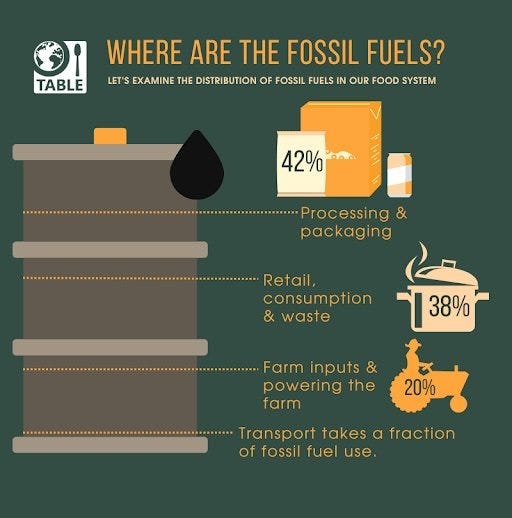

I came across this excellent Civil Eats op-ed by Anna Lappé that describes the way in which the fossil fuel industry is now using the food system.

First, we see the amounts of fossil fuel that lie behind a bag of potato chips (crisps to us Brits). Monocultivation of potatoes requires vast amounts of synthetic fertilizer and pesticides, irrigation, farm equipment, all of which depend on fossil fuels. Then there’s the energy demand of processing – sorting, washing, trimming, slicing, blanching, frying, seasoning. And that’s all before we get to the plastic packaging and what that requires – and the fuel costs to transport millions of plastic bags of chips to supermarkets, stores and vending machines.

This is fairly well known but what I didn’t know was that much of the fossil fuel-derived, carbon-intensive impact within the food system – including the production of the fertilizer, pesticide and plastic it uses – is not actually counted as food-related emissions (according to the IPCC and EPA).

On top of this, fertilisers and pesticides are now being coated with microplastics to slow their release. While this may reduce the amounts to be used, it adds in yet more plastic to the food system…and potentially into crops and foods and thus into our bodies. For the fossil-fuel industry though, it’s a new market.

On 11 March, The Guardian included a frightening story about the way microplastics (from routine sources) was already polluting the soil and hampering photosynthesis in crops, thus reducing yields of staple crops by up to 14%.

Cartel capture and the flip side of circularity

Circularity is usually a good thing when we have regenerative cycles that allow food to be grown and consumed in sustainable ecosystems where inputs and outputs are broadly in harmony.

But there’s a dark side where it derives from the production and response to harms.

At the turn of the century, we saw how the tobacco industry waded into the food system when its core business was threatened – by buying up food companies and manufacturing a new array of addictive ultra-processed products.

Now the pharmaceutical industry is reaping big rewards from the bad seeds sown by the food industry.

Both Big Pharma and Big Food are making massive profits from ultra-processed foods – one by producing and selling them, the other by providing the antidote to (some of) the harms they cause.

GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic and Wegovy are very expensive antidotes, accessible only to a few people who need them, and they have unknown long-term consequences.

But there’s more…

The UPF industry is adapting to this new world by developing products that are more acceptable to those who take these meds. Nestlé’s Vital Pursuit, for example, is

“intended to be a companion for GLP-1 weight loss medication users and consumers focused on weight management in the US. The products are high in protein, a good source of fiber, contain essential nutrients, and they are portion-aligned to a weight loss medication user's appetite.”

And so the cycle turns...

We pay many times over for unhealthy diets – the cost of (food) products, the cost of the ill-health they cause over time, the cost of the emissions used in producing them, the cost of the environmental harms of packaging – and now the cost of the remedy.

Just as we pay many times, large corporations profit many times over – from driving the problem, selling the antidote and from marketing a whole new array of products that help with the side effects caused by taking the antidote.

Imagine if cycles like this revolved around the generation of benefits, not harms.

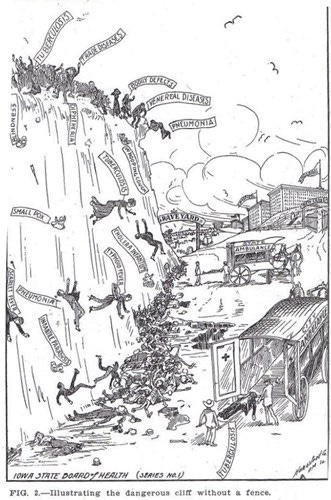

Fence or ambulance?

‘Twas a dangerous cliff, as they freely confessed,

Though to walk near its crest was so pleasant;

But over its terrible edge there had slipped

A duke and full many a peasant.

So the people said something would have to be done,

But their projects did not at all tally;

Some said, “Put a fence ’round the edge of the cliff,”

Some, “An ambulance down in the valley.”

To deal with anything that causes widespread ill-health, we need to prioritise prevention (the fence) but we also need accessible treatment for those who need it (the ambulance). The idea that – because we think we can produce enough ambulances, we don’t need to worry about the fence is not only crazy, it’s a direct abrogation of responsibility. Fences are guardrails that prevent public harm — and that’s the job of government.

Passing the buck

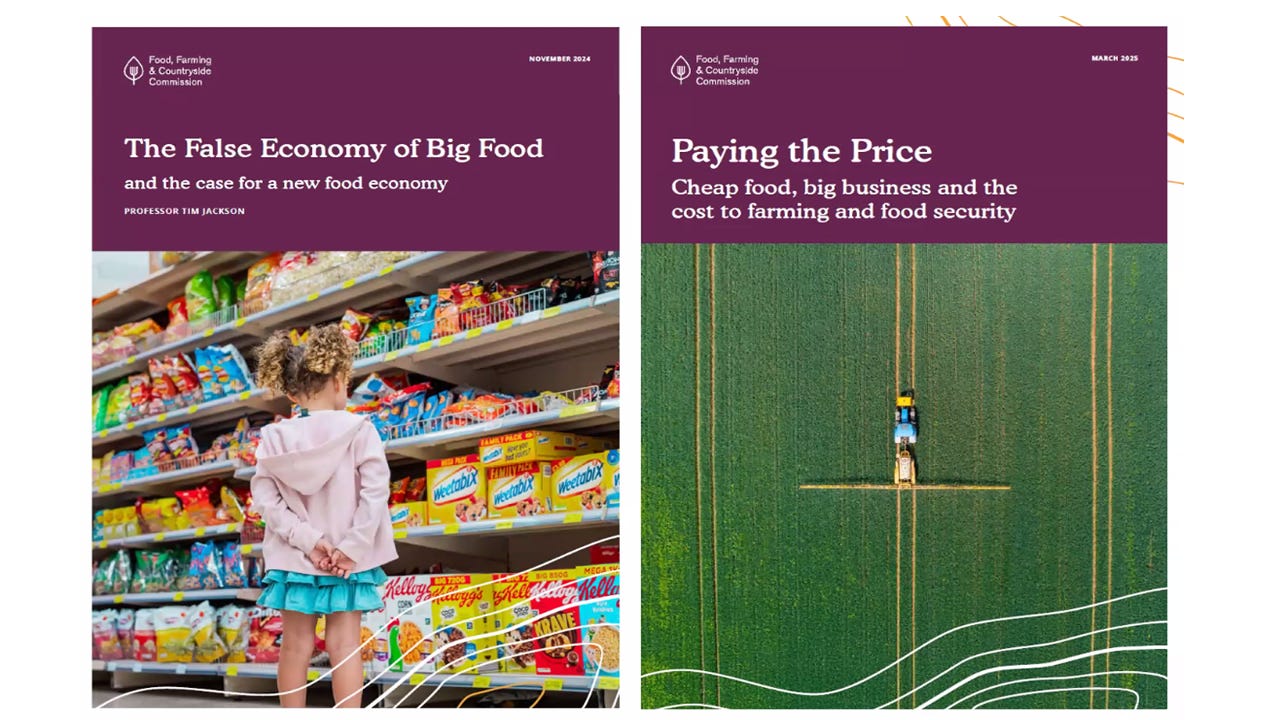

The Food, Farming and Countryside Commission (FFCC) has just released the second of its two reports – ‘Paying the Price: Cheap food, big business and the cost to farming and food security’. Like the first report, it’s packed with data, evidence and insights — concluding with a powerful set of recommendations.

The report describes how, despite improvements in productivity, UK farmers’ incomes haven’t changed in fifty years, They’re forced to scale up, intensify…or they’re forced to quit. The UK is more reliant on imports and a Big Supermarket cartel which prioritises unhealthy, cheap, ultra-processed products, as it squeezes farmers who are forced to produce animal feed or ingredients for industrial processes, not whole foods.

Across the board, in every corner of the food system, a handful of corporations dominate, most of which are subsidiaries of global agribusiness behemoths. They operate on ‘shareholder primacy’ which demands profit at every step, including using share buybacks to inflate stockmarket valuations rather than invest in improving the healthiness of portfolios. With little bargaining power, farmers and rural communities lose.

All of this is bad for our health, our environment, our climate, our food security and our ability to withstand shocks (resilience), whether driven by geopolitics, climate crisis, pandemics or whatever else.

This slow violence has been building for decades, behind the scenes, out of sight.

Reading this today and listening to the webinar, it’s clear we need a wider public conversation about values, what matters in food, diets and health – and the type of principles that should underpin a real food system transformation.

We need more of what Jon Alexander calls ‘liquid democracy’ — citizen assemblies that can help raise awareness of hidden costs and forge consensus on what our food system should look like. We need to shine a harsh light on the way power, in its various guises, has been used to drive commercial gain at our expense. Above all, we need politicians to step up and act, to set the rules and guardrails for a better food future.

Passing the book

A long time ago, I used to hitchhike up the motorway and camp in the Lake District. I’ve hardly been back since …not sure why.. but last weekend I saw what I’ve been missing. I was there to give my first talk on ‘Food Fight’ at the wonderful ‘Words by the Water’ literary festival but I also spent a lot of time wandering round the ridiculously beautiful shores of Derwentwater.

The great thing about a book project is you learn a lot researching and writing it, then you learn other things when trying to communicate it…and then you learn even more when trying to answer the thorny questions that come your way. In real time, under a spotlight, with nowhere to hide.

My first ever book signee was the brilliant James Rebanks who politely accepted my spidery scrawl — really looking forward to his lecture at the Oxford Literary Festival.

I also met Julian Baggini whose epic How the World Eats: a Global Philosophy had landed on my reading pile just as my book went to press. This of course meant I ignored it for several weeks. The last thing I wanted to read was anything about food!

But what a truly brilliant read it is…packed with fascinating insight, stories, angles. I really like the way he focuses on ‘food worlds’ (not food systems) to place ethics, values and culture, front and centre — and the thorough way he delved into the four pivotal domains — Land, People, Other Animals and Technology.

As a philosopher, Julian knows a thing or two about principles. His book ends with a list of seven – holism, circularity, plurality, food centrism, resourcefulness, compassion and equity.

If these were foundational to a food system (or food world), it would look and operate very differently to the one we have now.

‘Til next month!

Great, as usual, Stuart.

Claudio

Big Food is the next Big Oil. Investors and pension funds are waking up to the risks that we have known about for donkeys years.