Turn the power on

Eight months ago, I started this newsletter with a post about power.

Power is a lead character in ‘Food Fight’

For years, it’s been the elephant in the room in discussions about food system transformation. Huge and silent, bypassed…most people found a way to navigate around it.

If it is mentioned at all, we tend to see phrases like ‘managing power dynamics’ or ‘navigating power asymmetries’ in documents and statements. Less common, we may see ‘addressing power’

I hardly ever see an explicit statement of intent to actually CHANGE the balance of power in food systems.

Words matter – they’re the lifeblood of stories, the source of epistemic power.

Development and aid discourse is replete with co-opted and sanitised phrases and concepts – that’s not new. It’s so much easier to talk about managing things rather than changing them.

When it comes to tackling the commercial determinants of health or nutrition:

There’s the idea that conflicts of interest can be managed — they cannot, they need to be avoided

The idea that disclosure is enough — it is not (so long as the conflict remains).

The idea that companies can best regulate themselves. They cannot/will not – they need to be regulated by governments.

The idea that all ‘stakeholders’ in the food system want the same thing. They do not. Yes, many seek to maximise nutritional and health status but many others seek to maximise profit. Two goals that don’t sit well together.

We need to be more specific in our language and ditch clichés and slogans.

Which is why a recent paper by Dori Patay and colleagues is such a great and timely contribution. Check it out.

Finally, we can start to get beyond the co-option of ‘food system transformation’ language to suggest concrete approaches to drive real change.

So much energy is spent discussing what is really 'first-order' change – “surface-level adjustments to minor parameters, without fundamentally altering underlying structure or system dynamics”.

This is not transformation, it's tweaking at the margins – piecemeal incrementalism that just serves to maintain business-as-usual.

We need to go deeper to drive and enable:

Second-order changes – structural shifts that alter the underlying dynamics and behaviours in the system.

Third-order changes – shifts in actors’ mindsets, values and relationships that lead to profound and systemic transformations

*

There’s a second analogy about elephants in rooms – this one involves blind men, each one of whom believes, after touching one single part of the elephant, that he has figured out what it is.

It’s a parable about mental models or mindsets. As the Patay paper says, this is what we need to change if we are to get to real, sustained transformation.

To me, the acid test in any discussion of transformation is whether three Ps are all being taken seriously:

Purpose – profit…or people and planet?

Power – what forms, who uses it, for what purpose?

Process – what is actually happening (actions not words)?

Are things about to change?

The UNDP has a new Food and Power initiative with a white paper and 5-page brief and a report of a meeting held in Wilton Park, UK, expected next month.

Later this month, there is the UN Food Systems Summit + 4 Stocktake in Addis Ababa. Power is not on the main agenda and a proposal for a side event was not approved. This doesn’t bode well.

But let’s hope the positive energy from the UNDP initiative and this week’s webinar (organized by the UN Food Systems Coordination Hub, featuring the brilliant Jennifer Clapp), can be carried through to the main event. We’ll see….

Undocumented

Most discussions of power imbalances focus on the monumental power held by a few transnational corporations. Many millions of frontline workers who have very little power are overlooked.

There are so many stories. Here are three (the first two extracted from ‘Food Fight’)

Almeria. A large swathe of southern Spain is under wraps. Visible from space, the world’s largest concentration of greenhouses, covering 32,000 hectares (20% larger than Birmingham), produces 3.5 billion kilos of fruit and veg per year. Almeria’s plastic sea is the workplace of a displaced army of undocumented migrant workers who toil away without protection, in 40°C of heat and extreme humidity, surrounded by pesticide-coated crops. Over 120,000 men and women live, work and die here. Most of them come from West Africa, mainly Ghana and Senegal. Every day, a boat brings 30–40 new workers – over 12,000 every year. Others come from within Europe if their host countries crack down on migrants. Workers sleep in crowded camps, often without electricity and basic sanitation. They may only work a couple of days a week – for just 35 euros per day – but have to stick around for the next opportunity. It’s hazardous work -- one in three workers suffer from symptoms of pesticide exposure (neurologic disorders, headaches, paraesthesia, tremors), and many suffer from depression. If they can no longer work, they remain trapped in the settlements with nowhere else to go. Much of the harvest ends up on supermarket shelves in the UK. Here are the costs of our cheap year-round fruit and veg that that we don’t see – paid by people who we don’t see, who work in hothouses, way down the food chain. Out of sight, underpaid, unknown.

Beed is an impoverished district in southern India that’s home to 82,000 sugar-cane workers. Girls and young women, some of whom have been pushed into illegal child marriages, who cut cane all day in forced labour for sugar mills run by companies who supply Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. Up to one in three of them have had hysterectomies in order to keep working to pay off advances made by their employers (if they can’t work, they have to pay a fee). In March 2024, I read about this horror in a New York Times article. Over a year later, this Guardian article says the Indian health department is "closely monitoring the welfare of sugar cane labourers." Just monitoring?! No mention was made of the companies.

California. The third story comes from a Food Fix report on a raid by US federal agents (ICE) on a farm in California, which is terrifying. As Helena Bottemiller Evich concludes:

There’s a saying in U.S. agriculture: You either import your workforce or you import your food. This is not to defend the system we have – it’s been in desperate need of reform for a very long time – but I really wonder if ICE understands that they are playing with fire.

UK step forward

On 29 June, the UK Health and Social Care Secretary, Wes Streeting announced the requirement for all large food companies to report on the healthiness of their food sales.

The key part of this – unlike pretty much everything that’s gone before – is this will be mandatory reporting with the intention for mandatory targets to follow.

As Anna Taylor whose Food Foundation has been valiantly pushing for this for years says: “We are starting to see some real momentum now”

Wes Streeting also said:

“If everyone cut their calories by 215 calories a day, which is the equivalent of a bottle of Coca-Cola, we would halve obesity. It feels like an enormous challenge but actually the right steps in the right direction can be transformational.”

On 29 June, NESTA praised Streeting (on Bluesky) for adopting the policy they developed.

(Over two years ago, I wrote about the NESTA model (10% less junk is still junk) mentioning Kevin Hall’s pioneering work and suggesting the need to look at ultra-processing, not just HFSS…and certainly not just calories.)

Last week, Hall responded to NESTA’s Bluesky post:

“While I’m happy that our 2011 mathematical model was used by NESTA to estimate the step reduction in daily calories would be required to address obesity in the UK, I wish they had read our later studies. Unfortunately, a constant intensity intervention to reduce calorie intake typically results in exponential waning of the effect over time (not a sustained step reduction) and will therefore only result in about 20% of the weight loss they predicted.”

Later, he posted to say he’d had a productive meeting with NESTA:

“I strongly believe that policy interventions targeting the food environment are exactly the right approach. But when the promised effects of such policies are overstated and fail to materialize, public trust erodes. Fortunately, NESTA agreed to work with me to implement our updated model and provide more realistic estimates.”

Good outcome.

To me, this is yet another illustration of the need to move well beyond calorie-counting and linearity to get out of the mess we’re in. Our UPF-flooded food environments are a product of a systemic failure – which we need systemic solutions, recognizing plurality and diversity.

Nonetheless, things do seem to be happening…let’s see what emerges on the national food strategy…

Across the pond

Helena Bottemiller Evich (of Food Fix fame, referenced above) and Theodore Ross have just launched a lively new podcast called Forked

And here’s more on MAHA from Marion Nestle and Kevin Klatt. While swirling stories about food dyes and seed oils have grabbed headlines, systematic havoc is being wrought on science, on aid and on food assistance.

On the latter, Tracy Kidder’s New York Times essay on the new era of hunger pulls no punches.

Fighting talk

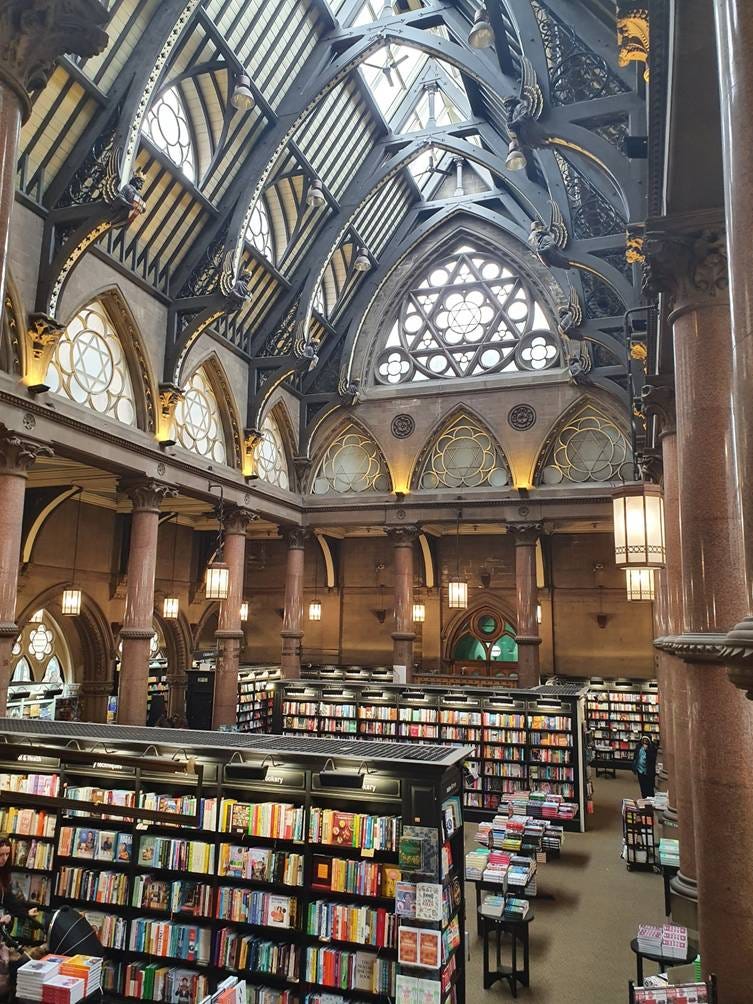

After weeks of criss-crossing the UK, I became becalmed in another heatwave last week. The last event in Bradford – my first time in the city – was fascinating. My talk was in the City Hall – a sprawling edifice built off the back of the city’s wool empire. This was followed by book signing in the nearby Wool Exchange (now Waterstone’s) which looks like this!

Last week, ‘Food Fight’ was shortlisted in The New Scientist as one of its ‘Best Books of 2025 So Far’ along with a punchy review. I quite like the way it hops between categories – food, health, society, environment, politics – but this was the first time I’ve seen it in ‘popular science.’

The same day it was listed in the US as a ‘must read’ book by the Next Big Idea Book Club for which I am very grateful…and very surprised! Civil Eats has also added it to their summer reading list. The US edition is out the day after Labor Day on 2 September.

One of my favourite recent podcast chats was with Kelly Brownell of Duke University. Kelly’s work has been hugely influential on (among other things) drawing the parallels between the tactics adopted by Big Food and Big Tobacco and how the former learnt from the latter.

And before that, it was great to have had the opportunity (thanks to the wonderful Christina Vogel) to speak at a City St George’s Food Thinkers webinar. I’ve long been a fan of this series, which always seems to be one level up.

As I can attest, having scrambled to field the barrage of incisive questions at the end!

See you in late July!

I loved your book Food Fight - thanks for writing it Stuart! Such a huge body of work and a useful and comprehensive history of food, food policy, food regulation and how it has impacted day-to-day life, work and health. It has been a useful read for me as I develop my knowledge of the history of global food security.