Ultra-processed power

The damage and the fightback

Last week saw the long-awaited launch of the Lancet Series on Ultra-Processed Food and Human Health.

In this post, I review the series – the challenges posed and solutions proposed – before developing a case study of food industry engagement and highlighting a few other relevant papers.

The first paper of the series focuses on the evidence of the harms generated by our UPF-saturated diets while the following two papers focus on the necessary response – the fightback. I mainly focus on the latter.

Each paper is excellent. Together, they represent a landmark.

The damage

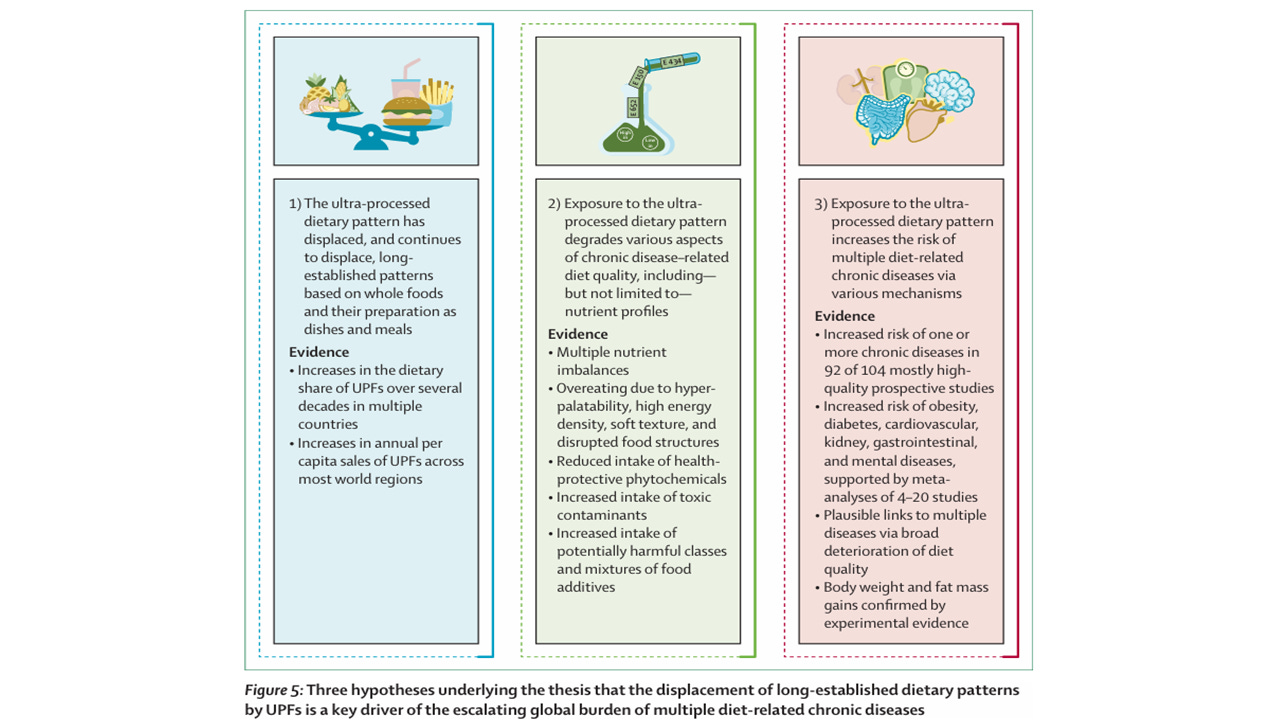

The first paper by Carlos Monteiro and colleagues examines the evidence for three key hypotheses: i) that UPFs displace traditional diets centred on whole foods, ii) that this reduces diet quality, and iii) that this trend and pattern increases the risk of multiple diet-related chronic diseases.

And finds:

‘The totality of the evidence supports the thesis that displacement of long-established dietary patterns by ultra-processed foods is a key driver of the escalating global burden of multiple diet-related chronic diseases.’

The fightback

The second paper by Gyorgy Scrinis and colleagues focuses on the policy response in relation to UPF production, marketing and consumption.

Crucially, they also examine policies to protect, incentivise, and support dietary patterns based on fresh and minimally processed foods, particularly for lower income households.

The policy response cannot be piecemeal or ad hoc. It needs to be bold and decisive involving concerted and comprehensive action that targets the product portfolios, marketing strategies, and sales structures of the corporate behemoths that control the global food system we have right now.

It also needs to go upstream to re-set the rules for foreign investment, and apply anti-trust regulations and restrictions on mergers and acquisitions in order to roll back corporate capture. Part of this will involve agricultural and trade policy reform to disincentivize monocultures (of maize, soy, sugar, palm oil) that supply cheap ingredients for UPF products and to incentivize and support diverse, local food systems.

The third paper (by Phil Baker and colleagues) addresses the structural and systemic challenge of radically overhauling the food system to put people and planet first.

It reminds us of something that can get lost, namely the simple fact that UPFs are extremely cheap to produce and highly profitable to sell.

The entire logic of the system – its core purpose – is not about human or planetary health, it’s about maximizing profit.

Purpose matters. Products and practices will always follow purpose. Innovation will always follow purpose. That’s why we’re in the mess we’re in.

And because UPFs are so profitable, corporations have become monolithic (choose any indicator you like) and quite adept at translating economic and financial power into political power.

The dark arts of corporate political activity are pretty well-known now. Sunlight has got in. Corporations, their front groups, multistakeholder initiatives and the researchers they fund use their power to block, delay and dilute governmental action in a strategic and global approach. (In Food Fight, I describe the five ‘Deadly Ds’ – doubt, distort, distract, disguise and dodge.)

Corporate political activity is often aided and abetted by compliant or inactive governments. Global northern governments fuel the UPF industry’s growth and profitability – often intervening on its behalf in the World Trade Organization and bilaterally through trade diplomats, to oppose UPF-related regulations of other governments.

Corporate capture goes even further – beyond markets, finance and politics into science and the media.

I thought I knew a thing or two about conflicts of interest in food and nutrition research but I was stopped in my tracks by this stat. Nearly 3,800 studies published between 2008 and 2023 disclosed funding or interests naming UPF manufacturers. Of these, a third focused on energy balance or physical activity, a known corporate scientific strategy (‘distort’) intended to shift blame away from products and corporate practices.

Do the math – that’s an average of one industry-funded study published on every working day of those 15 years!

This kind of power also translates into epistemic or discursive power – via influence on the media (mainstream and social).

Phil and his team do a brilliant job in showing what needs to be done to turn the juggernaut around – how to reduce UPF industry’s political power by protecting food governance from corporate interference, implementing robust conflict of interest safeguards (in policy, research, and professional practice), by cleaning up lobbying and ending UPF industry sponsorship and funding.

But beyond, to activate citizen and civil society power – highlighting ways to mobilise a global public health response by building advocacy coalitions, generating legal, research, and comms capacities to drive policy change and ensure a just transition to a food system in which health, equity, and sustainability prevails over corporate profit.

‘Do the right thing. Not tomorrow. Not next year. Today!’

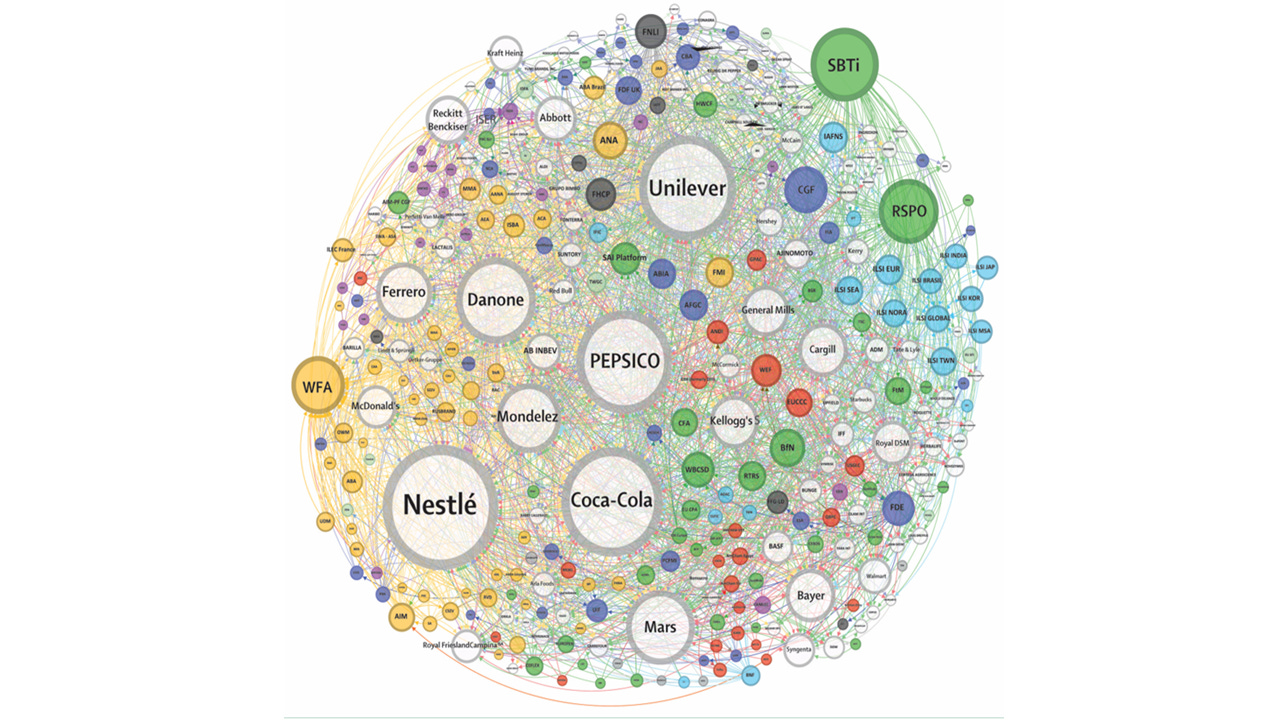

Paper 3 includes this ‘power map’ — showing the interest group memberships of corporations. Eight corporations dominate — the largest of which, Nestlé, is a member of 137 of the 207 groups around the world.

Nestlé is the world’s biggest food company with a long history – expanding from 80 factories in the 1920s to 340 factories across 76 countries in 2023, supported by 24 research and development centres serving 188 markets.

Let’s take a look at what it’s been up to in recent months.

A recent Public Eye investigation into sugar-boosted Nestlé products being sold in Africa found that 90% of 100 Cerelac product samples in 20 countries in Africa contained added sugar. Similar products in global-northern countries contain no added sugar. On average, each analysed serving contained nearly 6g added sugar (1.5 sugar cubes) with the highest (7.5g, almost two sugar cubes) found in a Cerelac product for six-month-old babies being sold in Kenya.

Shocking in itself – but even more so in the context of similar findings over a year ago:

The amount of sugar found in products from African countries was 50% higher than those in products sold in Asia and Latin America. An open letter was sent to the corporation — concluding with the plea in the title above.

*

Here’s a recent paper on Nestlé and commercial determinants of infant health in Africa.

Nestlé sponsored the Africa Food Prize, an initiative of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, as a commitment to address nutrition, food insecurity, and hunger on the continent.

Nestlé has supported the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA) Centre of Excellence in Sustainable Food Systems, funding research on food and nutrition as well as hosting and mentoring postgraduate student

Nestlé co-funds an astroturf group (a fake grassroots organization) called ‘Americans for Ingredient Transparency’ whose goal is to lobby the US Congress to override new state laws, like California’s AB1264, which will ban the unhealthiest ultraprocessed foods from school meals.

Nestlé and Tufts University recently promoted their partnership on social media.

(I asked if Tufts has a private sector engagement policy, an institutional position on conflicts of interest. Twice. No response, just a reiteration of how proud they were.)

Going global

Any response to corporate capture of markets and politics has to be global – just like the problem and the industry.

UN agencies have a big role to play – in developing technical guidance, integrating UPF-based metrics into surveillance systems and establishing global and national targets on reducing the dietary share of UPFs.

Paper 3 makes the case for an international policy framework – like a WHO convention – to empower national government regulators. UN human rights bodies could interpret treaty provisions in relation to UPF-related harms. Though the Lancet Series focused on human health, there are huge implications of our UPF-dominated food systems for unfolding biodiversity, plastics, and climate crises.

So how is the United Nations responding?

Is it actually united in its engagement with industry – especially where potential partners are directly implicated in driving harms that relate to its mandate?

Well, the overarching UN Business Compact is limited. Why, for example, does it not include health in its list of criteria (along with human rights, labour, environment, anti-corruption, terrorism, crime, arms, pornography, gambling, tobacco)?

UN agency positions also differ quite a bit on industry engagement. Again, looking at one corporation.

UNICEF and WHO do not engage with Nestlé but UN Women, UNESCO do.

FAO’s guidelines contain exclusionary criteria including: ‘manufacturers of sugar-sweetened beverages and/or high in fat, sodium, and/or sugar foods’ but it’s not clear whether this precludes sharing platforms at policy conferences.

The CGIAR is not immune. The Chair of the Board of the CGIAR was a Board member of Nestlé for her full term. She stepped down from the CGIAR position in July, but continues in the Nestlé post.

There’s an interesting approach to compensation for the latter. Apart from the eye-watering honorarium (over $500,000 per year), half of it comes in the form of shares. Which board member would vote for anything that reduces profit, that reduces the share of its portfolio comprising ultra-profit foods?

UNICEF’s position – like that of Nutrition International – is unequivocal. Two beacons of light, highlighted here.

*

Meanwhile, Nestlé itself has had an interesting year. The CEO Laurent Freixe was fired recently for ‘a romantic relationship with a direct subordinate’ (yes, you read that correctly – ‘subordinate’).

Dalliances with ‘subordinates’ are apparently not unusual in the thin air of Big Food leadership. The CEO of McDonald’s was fired in 2019 after a consensual relationship with an employee (…later upgraded to four employees!)

I digress…but if we’re in any doubt about the future of Nestle, there’s this. The new CEO will make a ‘fresh start’ but one in which ‘everything will become faster, developing and launching new products, and renovating existing ones, to more marketing….growth is the focus.’

On purpose and partners

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) between commercial actors and governments or other non-profits have little evidence of effectiveness – though you wouldn’t think so, given the frequency they’re promoted.

A recent study interrogates the role and legitimacy of food industry actors as partners in policies to improve the food environment. Key ‘fault lines’ that emerged included: i) uninterrogated assumptions that partnerships are effective, ii) the role of exclusive social networks, iii) the voluntary nature of partnerships, iv) data ownership, v) control of narratives and vi) the centrality of political ideology.

Another recent study interrogates ‘multistakeholderism’ – the notion that global public issues should be addressed by all those who affect or are affected by an issue (as espoused recently in the United Nations Food System Summit event and process.) Like PPPs, multistakeholder governance (MSG) has limited evidence of effectiveness and a high risk of corporate capture.

This study analysed responses to WHO consultations related to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) to examine how actors construct or contest the legitimacy of MSG. Results highlighted big differences. Proponents of MSG, primarily industry-affiliated organisations, cited industry expertise and resources as key justifications, while non-profit and academic respondents tended to argue against industry inclusion in MSG, referring to conflicts of interest and potential corporate capture of the policy process. The paper concludes with a plea to WHO and other UN agencies to critically examine the evidence on multistakeholder approaches and to use unambiguous terminology when discussing them.

Industry opposition

The UPF industry – and its investors – will not take all this lying down. Several tropes have emerged over the years, including:

Not enough evidence, more research needed

Nova is sub-optimal – some UPFs are healthy

UPFs and Nova are ideological constructs

There’s nothing wrong with ‘food processing’

Unhealthy diets are due to nutrient imbalances, not ultra-processing

Unhealthy diets are due to poor choices, a lack of awareness, poor education

An unhealthy diet is an individual responsibility

UPFs are convenient

UPFs generate economic growth

UPFs can be reformulated to make them healthy

We’re the experts, leave it to us.

Nanny state regulations restrict our freedom

The industry can regulate itself

Regulation stigmatizes poor and vulnerable individuals who can only afford cheap UPFs

There are clear responses to each one of these – but that’s a later post!

That said, I have to mention what is surely one of the worst media articles. Somehow this one, in just a few paragraphs, manages to capture most of the above list. The journalist had clearly not even read the abstracts, let alone the papers, as she described ‘another new study’. She repeatedly conflates processing with ultra-processing before accusing anyone working to improve diets as being middle-class faddists out to stop people who are poor from buying cheap food. The ethics of this ‘let them eat cake’ position are not questioned. She conveniently ignores the repeated need to balance any regulation of harmful UPFs with policies to improve access and affordability of low-income families to a healthy diet.

This recent paper is worth checking out.

The UPF-RAN

The Lancet Series is pivotal in laying out the evidence of damage and the options to respond. But it’s also a springboard to more action. The third paper describes the launch of UPF-RAN

“A global UPF action network could build on existing advocacy and policy responses - especially those in Latin America and Africa - and bring together civil society organisations and movements, experts, UN agencies, government leaders, and donors, to pool resources, advocate for policy change, and stand up to corporate power.”

Check it out…

*

This is the first birthday of ‘FOOD FIGHT FILES’ Since last November, I’ve posted 27 newsletters, a couple every month (…though don’t hold me to it!).

I hope you enjoy it.

Thanks for taking the time to dig in – and do let me know what you think.

Thanks Maria....there's a paper coming out (hopefully) soon on this...will wait for that before posting on this. Thanks!

Your work is so important! I’ve added your book to my wish list